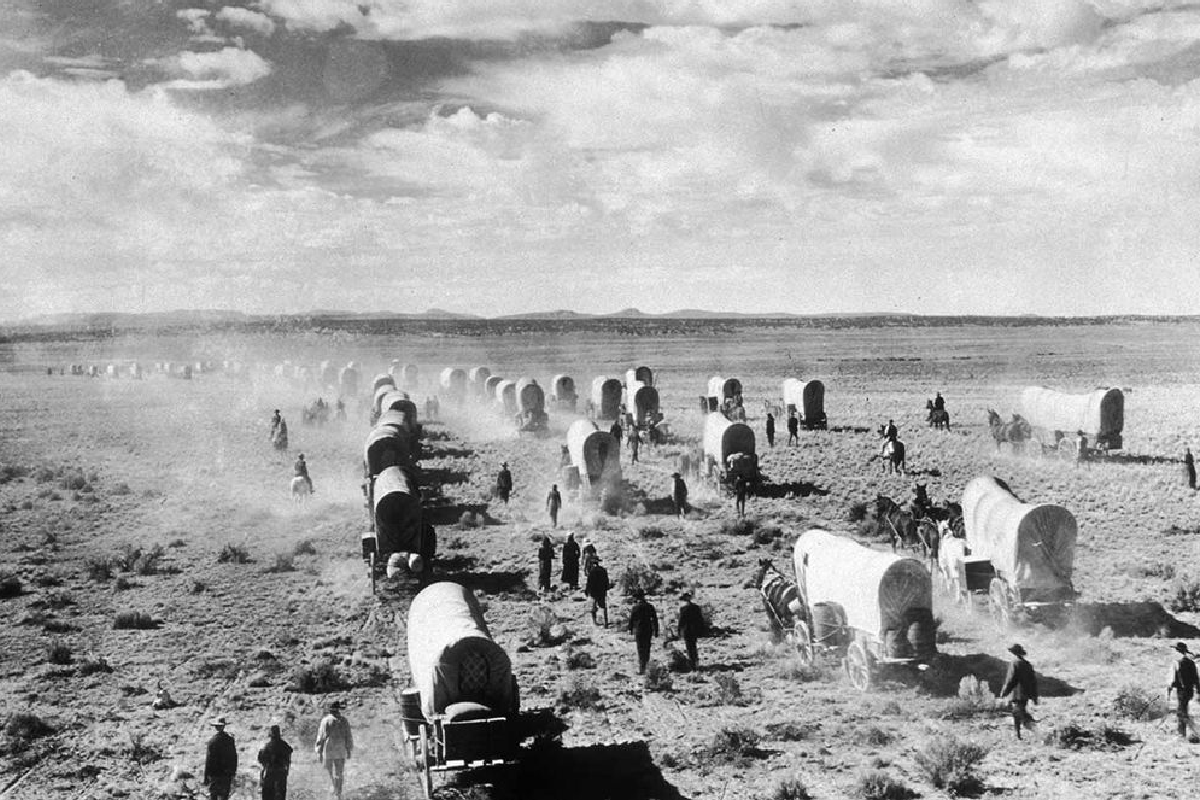

As traffic on the Oregon Trail increased, a bustling industry of frontier trading posts sprang up to supply food and equipment for the five-month haul. In popular jumping-off points like Independence, Missouri, unscrupulous merchants made a killing by conning frightened pioneer families into buying more provisions than they actually needed. The overloading meant that many sections of trail became junk heaps filled with discarded food barrels and wagon parts. Broken down prairie schooners and dead draft animals also littered the roads, and it wasn’t unusual to see personal items like books, clothes and even furniture. Fort Laramie in Wyoming eventually became known as “Camp Sacrifice” for its reputation as an Oregon Trail dumping ground. During the Gold Rush of 1849, pioneers reportedly abandoned a whopping 20,000 pounds of bacon outside its walls.

Contrary to the depictions of dime novels and Hollywood Westerns, attacks by the Plains Indians were not the greatest hazard faced by westbound settlers. While pioneer trains did circle their wagons at night, it was mostly to keep their draft animals from wandering off, not protect against an ambush. Indians were more likely to be allies and trading partners than adversaries, and many early wagon trains made use of Pawnee and Shoshone trail guides. Hostile encounters increased in the years after the beginning of the Civil War, but statistics show only around 300 settlers were killed by natives between 1840 and 1860. The more pressing threats were cholera and other diseases, which were responsible for the vast majority of the estimated 20,000 deaths that occurred along the Oregon Trail.

“Prairie fever” is an affliction usually attributed to isolation Elizabeth Markham seems to have gone insane. Or, perhaps she went insane before they embarked. Six of her children died before reaching the age of three. She was traveling to Oregon with her husband, Samuel and five children.

On September 15th,1847 along the Snake River Canyon she decided she could go no further and informed her family she was going no further. After some argument Sam Markham took the family and moved on. Later that day he decided to send his eight-year-old son John, back to check on her. Hours later she returned alone and told them she’d beaten the boy to death with a rock. He rushed back to find his son clinging to life. Meanwhile, Lizzie set fire to one of the wagons. Fortunately, the fire was extinguished.

John survived and they made it to Oregon where she gave birth to two more children. But soon, Elizabeth and John were divorced and he went to California. She re-remarried again and divorced again. She became a poet and much of her poetry was devoted to the travails of marriage. Her surviving children later said she was an abusive mother. Apparently, her sanity never returned,

Along with painting messages and mottos on their wagon canvasses, pioneers also developed a tradition of carving their names, hometowns and dates of passage on some of the stone landmarks they encountered during their journey west. One of the most notable prairie guest books was Independence Rock, a 128-foot-tall granite outcropping in Wyoming dubbed “The Register of the Desert.” Thousands of travelers left their mark on the rock while camping along the nearby Sweetwater River. Those in a hurry sometimes even paid stonecutters a few dollars to carve their messages for them. In addition to Independence Rock, pioneers also left behind signatures on Register Cliff and Names Hill, two other sites in Wyoming.

Only around 80,000 of the estimated 400,000 Oregon Trail emigrants actually ended their journey in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Of the rest, the vast majority splintered off from the main route in either Wyoming or Idaho and took separate trails leading to California and Utah. The California Trail was eventually traveled by some 250,000 settlers, most of them prospectors seeking to strike it rich in the gold fields. The Utah route, meanwhile, shuttled roughly 70,000 Mormon pilgrims to the lands surrounding Salt Lake City.

Only around 80,000 of the estimated 400,000 Oregon Trail emigrants actually ended their journey in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Of the rest, the vast majority splintered off from the main route in either Wyoming or Idaho and took separate trails leading to California and Utah. The California Trail was eventually traveled by some 250,000 settlers, most of them prospectors seeking to strike it rich in the gold fields. The Utah route, meanwhile, shuttled roughly 70,000 Mormon pilgrims to the lands surrounding Salt Lake City.

With the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in Utah in 1869, westward wagon trains decreased significantly as settlers chose the faster and more reliable mode of transportation.

Still, as towns were established along the Oregon Trail, the route continued to serve thousands of emigrants with “gold fever” on their way to California. It was also a main thoroughfare for massive cattle drives between 1866 and 1888.

By 1890, the railroads had all but eliminated the need to journey thousands of miles in a covered wagon. Settlers from the east were more than happy to hop a train and arrive in the West in one week instead of six months.

The last wagon widely known to have traveled the length of the Trail was driven in 1906 by Ezra Meeker, an aging Oregon Trail emigrant who was conducting a one-man publicity campaign to remind people of the historic significance of the Oregon Trail. However, visitors at the End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center claimed because their family couldn’t afford the train fare, they traveled the Trail by wagon as late as 1912.